His own conversation was ever of human things. The problems he discussed were, What is godly, what is ungodly; what is beautiful, what is ugly; what is just, what is unjust; what is prudence, what is madness; what is courage, what is cowardice… - Xenophon

There is nothing more human than questions of morality. We share our instincts for survival with the animals. Gravity and other physical forces affect rocks and people alike. Even logic and discursive reasoning can be, to some degree, imitated by artificial intelligence.

But none of these other entities share the human being‘s innate sense of oughtness, that things ought to be a certain way (but often aren’t) and that we ought to behave a certain way (but often don’t). We experience mental and emotional anguish to varying degrees when we deliberately contradict how we know we ought to act, that is, until we’ve successfully numbed that sense of oughtness into nonexistence.

Also unlike the animals, we intuitively grasp (at least in our more lucid moments) that acting according to this sense of oughtness is key to discovering and fulfilling the purpose for which we exist.

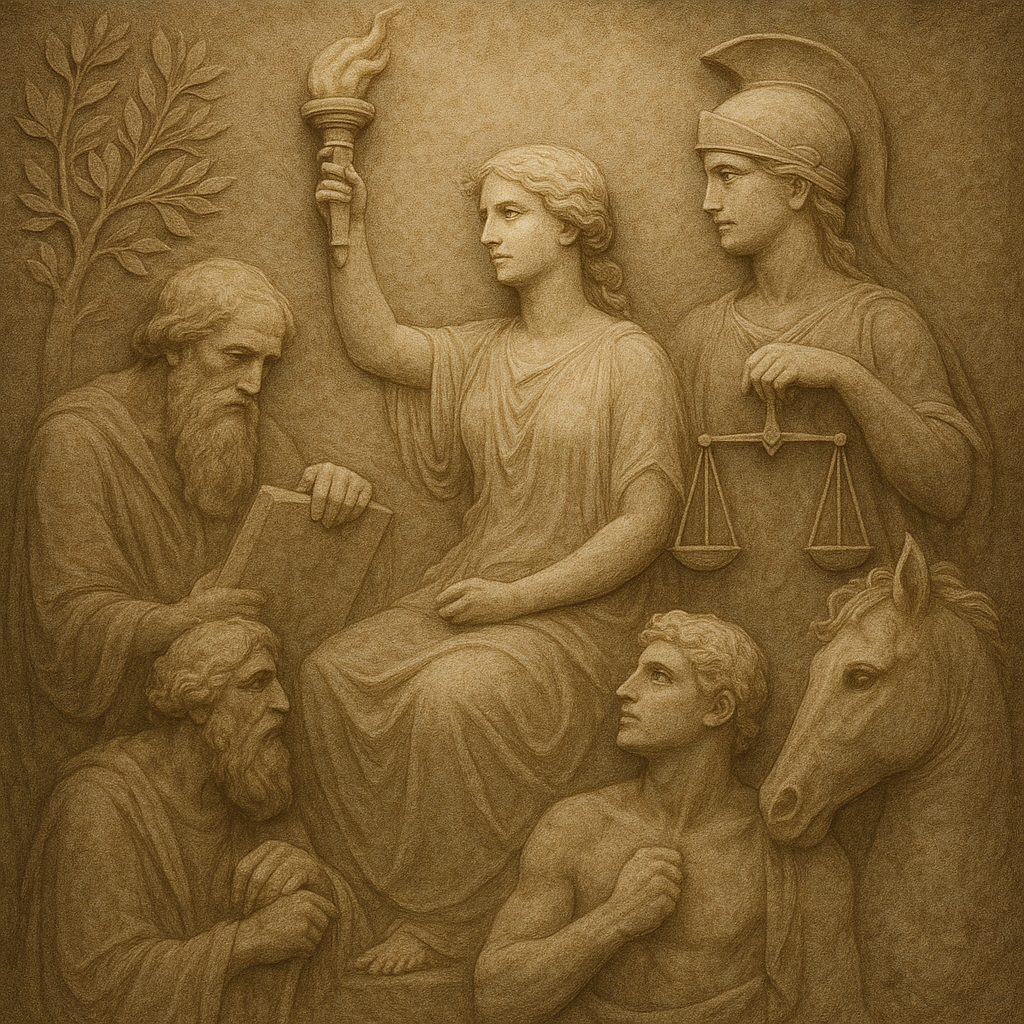

That is why Socrates (the “he“ whom Xenophon refers to in the introductory quote) considered godliness, justice, beauty, and courage as among the most human things. They are, in fact, uniquely human features and essential to what it means to live a human life. They are easy to overlook because they don't promise wealth or power, and mere survival is possible without them.

And yet, despite this, the cultivation of these virtues is central to building a life worth living. Power means nothing if it is not used for the good of others. Wealth is only fully enjoyed when it is shared. And survival for its own sake means little; it’s what one does with that life that counts.